The last Widnes Sci Bar was delivered by Bob Roach (and his power point is appended in the side bar). Bob took us on a journey through the social and economic development of Widnes infused with the chemistry of the Leblanc process, and the challenges facing the early pioneers of chemical engineering. Bob's "credentials" give him an interesting "take" on the subject: he worked in the industry in the '60s (19! he's not that old!) and he has lived and worked amongst the community in Widnes, developing an affinity for the town and its citizens past and present: the view of the old and the new (soon to be added to) Mersey crossings from Ross Bullock's nice web site seems a suitable image (top LHS). My own interest in this subject has some overlaps, but I am particularly interested to see whether a detailed analysis of the origins, the growth and subsequent decline of the Chemical Industry in the "greater" Merseyside region provides us with the insight for harnessing the developments in Biotechnology: currently under discussion under the banner of "Synthetic Biology" (take a look at the government's recent investment at Manchester University's Centre for Synthetic Biology of Fine and Speciality Chemicals). After all, one of the fundamental justifications for studying history is to avoid the mistakes of the past and perhaps more importantly anticipate the problems that might scupper a new commercial venture!

The last Widnes Sci Bar was delivered by Bob Roach (and his power point is appended in the side bar). Bob took us on a journey through the social and economic development of Widnes infused with the chemistry of the Leblanc process, and the challenges facing the early pioneers of chemical engineering. Bob's "credentials" give him an interesting "take" on the subject: he worked in the industry in the '60s (19! he's not that old!) and he has lived and worked amongst the community in Widnes, developing an affinity for the town and its citizens past and present: the view of the old and the new (soon to be added to) Mersey crossings from Ross Bullock's nice web site seems a suitable image (top LHS). My own interest in this subject has some overlaps, but I am particularly interested to see whether a detailed analysis of the origins, the growth and subsequent decline of the Chemical Industry in the "greater" Merseyside region provides us with the insight for harnessing the developments in Biotechnology: currently under discussion under the banner of "Synthetic Biology" (take a look at the government's recent investment at Manchester University's Centre for Synthetic Biology of Fine and Speciality Chemicals). After all, one of the fundamental justifications for studying history is to avoid the mistakes of the past and perhaps more importantly anticipate the problems that might scupper a new commercial venture! In the beginning. Bob began his talk with a potted history of the chemistry of the Leblanc process (RHS and in more detail in Bob's presentation slides) and the bad timing (for Nicolas Leblanc!) who benefited from the patronage of Philippe, Duke of Orléans during the late 18th Century in France, which enabled him to collect the prize money offered by Louis XVI and the French Academy of Sciences. This was an attempt to reduce France's dependency on imports for its alkali production, since France had just emerged from a war with Russia. However, scholars of History will look at the dates and realise that a close relationship with the monarchy in France in the 1790s, was a bad plan; and one that was liable to lead to you losing your livelihood, if not your head! And so France's missed opportunity to capitalise on the Leblanc process was Britain's gain. I am pretty sure that since the French Revolution, this story has been repeated in industry a number of times, and the fact that the UK, the country from which Graphene came, holds around 50 patents whilst China, South Korea and the USA hold between them 5 000 on applications of Graphene, suggests that we haven't read our own history (you can read a short Guardian article here on this)!

The people. Bob provided us with a charming insight into the shakers and movers of the Chemical Industry, from the "visionary" pioneering character of John Hutchinson, who marshaled brilliant young chemists while striking tough business deals, to the brilliant inventiveness of the polymath William Gossage. Then there was the flamboyant genius, if not somewhat precocious, Dr. Ludwig Mond (LHS), born in Germany, but in death a British citizen. However, Bob was keen to point out that on a number of fundamental issues of judgement; the otherwise brilliant, Swiss Industrial Chemist Ferdinand Hurter, was not infallible! Importantly, he persisted with the predictability and longevity (as he thought) of the Leblanc process, when the new wave of industrialised electrochemistry was lapping at the factory walls! We were also reminded by Bob of Hurter's (and his colleague at the Gaskell-Deacon works, Vero Charles Driffield) major contributions to Photography. In fact they were jointly awarded the Progress Medal of the Royal Photographic Society in 1898).

The people. Bob provided us with a charming insight into the shakers and movers of the Chemical Industry, from the "visionary" pioneering character of John Hutchinson, who marshaled brilliant young chemists while striking tough business deals, to the brilliant inventiveness of the polymath William Gossage. Then there was the flamboyant genius, if not somewhat precocious, Dr. Ludwig Mond (LHS), born in Germany, but in death a British citizen. However, Bob was keen to point out that on a number of fundamental issues of judgement; the otherwise brilliant, Swiss Industrial Chemist Ferdinand Hurter, was not infallible! Importantly, he persisted with the predictability and longevity (as he thought) of the Leblanc process, when the new wave of industrialised electrochemistry was lapping at the factory walls! We were also reminded by Bob of Hurter's (and his colleague at the Gaskell-Deacon works, Vero Charles Driffield) major contributions to Photography. In fact they were jointly awarded the Progress Medal of the Royal Photographic Society in 1898).My good friend Professor Walter Blackstock who attended the talk has provided me with some links to two books that Bob referred to, both are available to view online.

"The white slaves of England, being true pictures of certain social conditions in the Kingdom of England in the year 1897" by Sherard, Robert Harborough, 1897, available to read at:

https://archive.org/details/

and

"Some founders of the chemical industry; men to be remembered" by Allen, J. Fenwick (John Fenwick), 1907.

Contents:

I. William Gossage.--II. Josias Christopher Gamble.--III. James Muspratt.--IV. Andreas Kurtz.--V. Henry Deacon.--VI. James Shanks.--VII. Christian Allhusen.--VIII. Peter Spence.--Appendix I: Mr. William Keates

https://archive.org/details/

The town grows. Before the boom in the Leblanc trade in Widnes, the town, a collection of hamlets in Appleton, Farnworth and Ditton, was known as Woodend. Interestingly, the population figures tell a tale of massive job creation: from around 2 500 in 1841, to 25 000 in 1881. The interviews with Alkali workers in Sherard's book are often tragic: noting of course its controversial reception and the critical comments in Hardie's take on the Chemical Industry. Thanks again Walter for the link:

The town grows. Before the boom in the Leblanc trade in Widnes, the town, a collection of hamlets in Appleton, Farnworth and Ditton, was known as Woodend. Interestingly, the population figures tell a tale of massive job creation: from around 2 500 in 1841, to 25 000 in 1881. The interviews with Alkali workers in Sherard's book are often tragic: noting of course its controversial reception and the critical comments in Hardie's take on the Chemical Industry. Thanks again Walter for the link:Hardie's "A History of the Chemical Industry in Widnes" is currently for sale s/h on Abe for £9.99 plus £2.80 postage - a good price!

http://www.abebooks.co.uk/

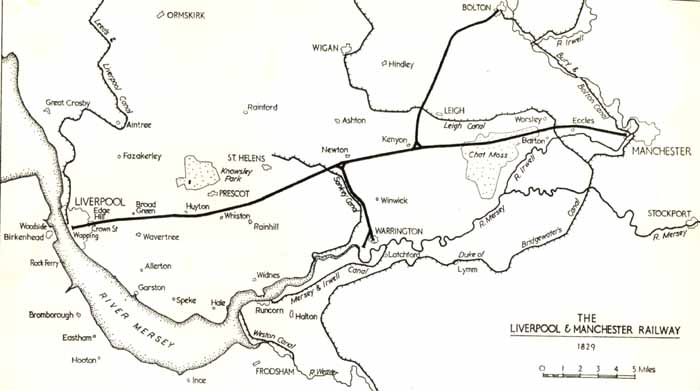

Science and Society. Bob covered an enormous topic in a relatively short time (time flies when you are having fun!) and for me it brought back memories of school Geography lessons: Hutchinson's visionary instincts about location, resources, supply chains and transport, are great lessons in business location. The consequences of unfettered growth in the absence of a parallel programme of Health and Safety legislation and the poor consideration for sustainability, are lessons that we need to take form this story. Then of course we have the rise of worker's rights, pay and conditions and the rise of Socialism as a third way from the Victorian "toing and froing" of Whig and Tory politics (sound familiar?). These events paved the way for the latter day, generous and ground-breaking terms of employment given to employees at Unilever and ICI in this region in the middle of the last century. Finally, let us not forget the influence of two World Wars on the Chemical Industry: this mix of politics, society, economics, geography, chemistry, culture, inward migration, work-life balance and education were all touched on in Bob's fascinating presentation

Lessons from our Legacy. As a final, personal thought, we have our Catalyst Museum (LHS) in Widnes which is the Guardian of the tremendous legacy of our region's Chemical Industry heritage: good and bad! But I believe the History of the Chemical Industry in Widnes is a story that should be understood and promoted much more widely. The events that Bob surveyed for us, provides so much valuable wisdom for those charged with the responsibility of investing in, or regulating, the industries of the future; whether it is Biotechnology, Smart Materials, Software, Hardware, Electronics, Nanotechnology, Renewable Energy etc. etc. The History of the Chemical Industry in Widnes, like that of the Textile Industry in Lancashire, or the Shipping Industry in Liverpool and Glasgow, holds so many valuable lessons for us as we try and build new sustainable industries, and create new jobs for the coming generations.

Lessons from our Legacy. As a final, personal thought, we have our Catalyst Museum (LHS) in Widnes which is the Guardian of the tremendous legacy of our region's Chemical Industry heritage: good and bad! But I believe the History of the Chemical Industry in Widnes is a story that should be understood and promoted much more widely. The events that Bob surveyed for us, provides so much valuable wisdom for those charged with the responsibility of investing in, or regulating, the industries of the future; whether it is Biotechnology, Smart Materials, Software, Hardware, Electronics, Nanotechnology, Renewable Energy etc. etc. The History of the Chemical Industry in Widnes, like that of the Textile Industry in Lancashire, or the Shipping Industry in Liverpool and Glasgow, holds so many valuable lessons for us as we try and build new sustainable industries, and create new jobs for the coming generations. Thanks Bob for a thoroughly enjoyable evening and Walter Blackstock for the information: I would stress that these are my own views.

No comments:

Post a Comment